Hot valley where I knelt down so often

I saw two small white clouds

so close to the Earth.

Murmuring ‘su’ I am the second part of my name

I wished I could flow in this white pebbled stream bed.

I was told that the sea is also ‘su’

but life in the sea is different.

My dreams went to the west of this island

where the water moths were making love.

As a child I knew the colour of their bodies,

now I have nothing but wind left in the palm of my hand.

You were a marshy valley and I knelt down beside you

and in your lap trees grew by themselves.

I was the salt in your face.

Mehmet Kansu, “Ode to Mesarya”

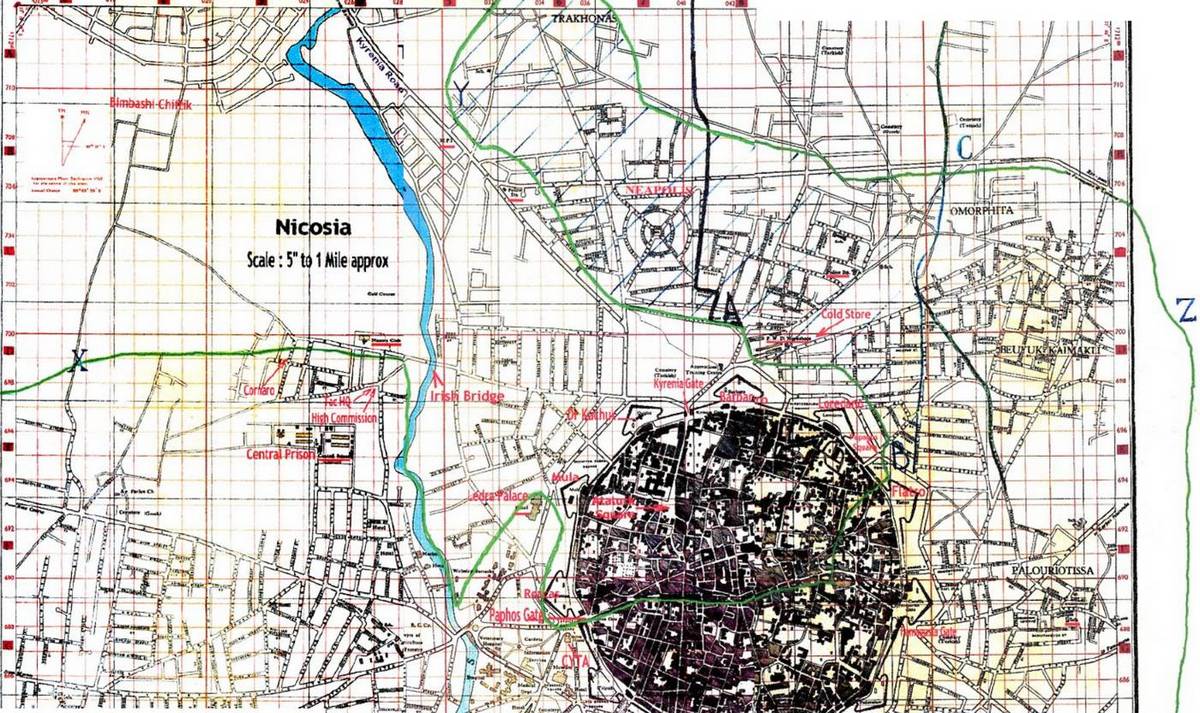

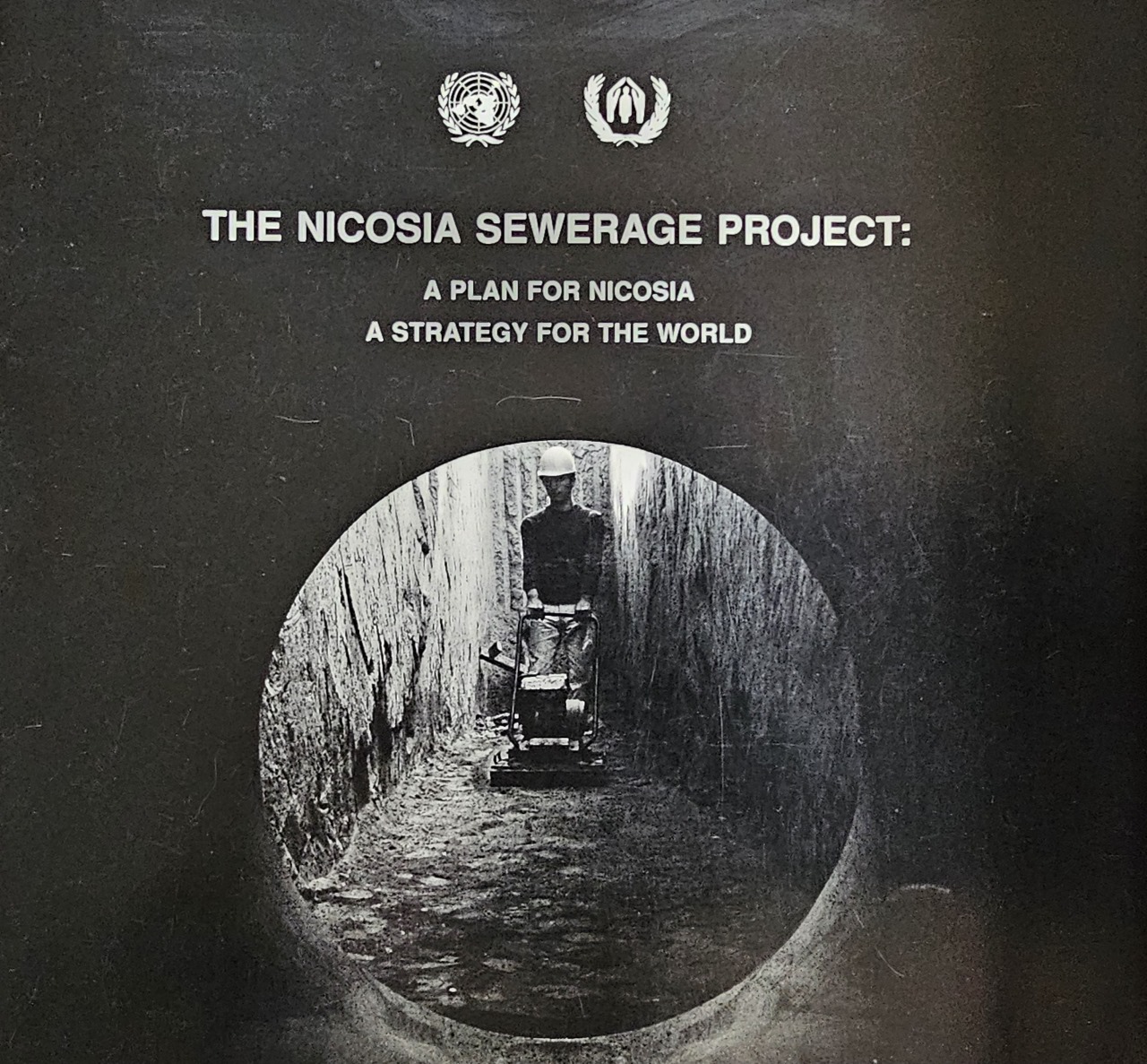

The Green Line divides not only the two communities, but also the Pedieos River, the longest river on the island. Conversely, the first major confidence-building measure following the conflict was focussed on transboundary water cooperation: the agreement for the common Nicosia sewerage system (1978)

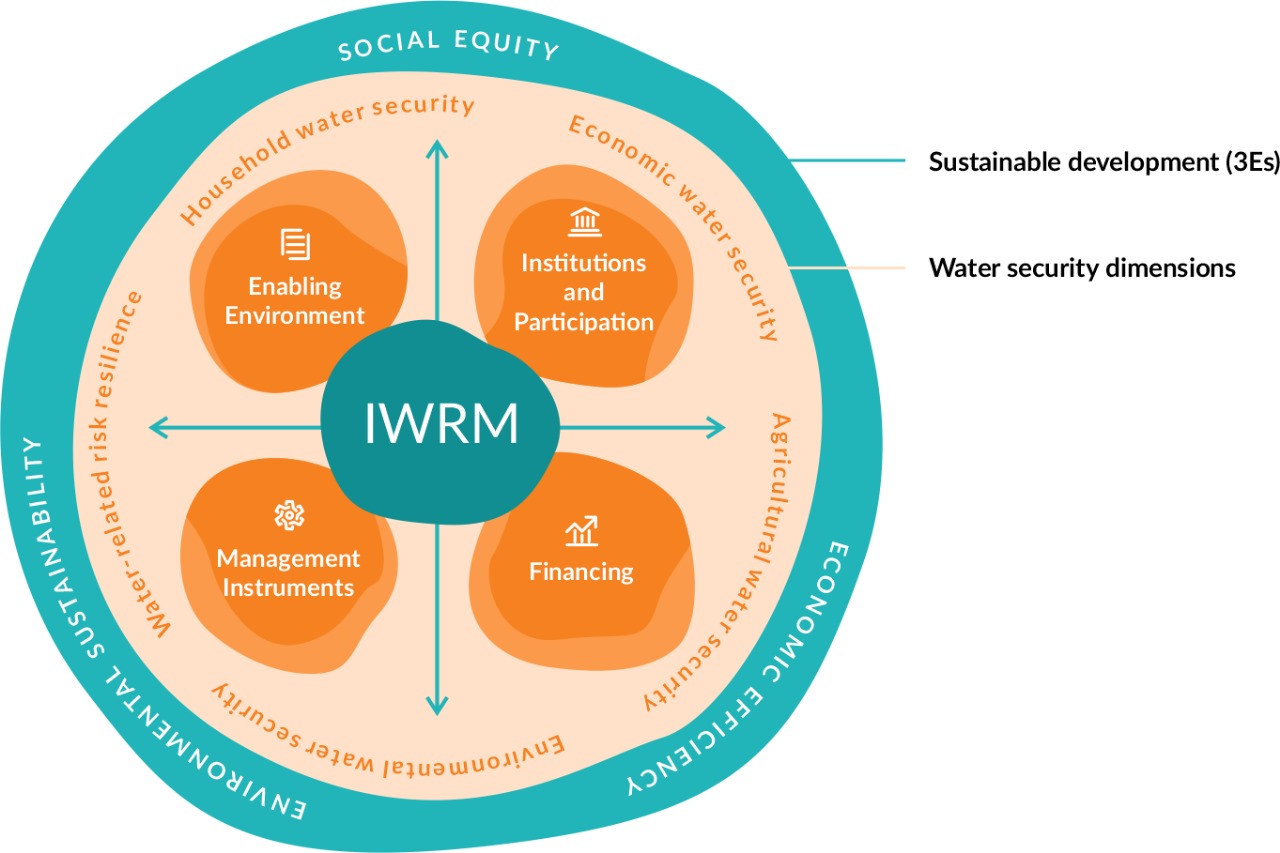

An IWRM-centred transboundary approach is sorely needed in Cyprus, because aside from Pedieos and smaller rivers, the Green Line also transects two of the major aquifers on the island. In addition, Cyprus is among the 5 most water-stressed countries in the world, while Climate Change is making this water stress even worse. The island, which already has one of the lowest amount of available freshwater resources per capita in the EU, has already experienced severe droughts (in 2008, there was a need to import freshwater from Greece).

Nicolas Jarraud

Discover MoreThe content of this blog is the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.